Print of the month

No. 29, May/June 2009

The Yale Center ‘Panorama’

This month’s subject is an artefact recently acquired by the Yale Center for

British Art in New Haven which uses printed images to present a kind of moving

panorama of a strikingly modern kind. It comprises a leather-bound wooden box

with a screen and two rollers; by rotating the ends of these, it is possible to

view frame by frame through the 'screen' of the box a series of images which

were evidently cut from a sheet and pasted together into a long continuous

strip. This panorama, which has a truly popular appearance, must date—on

internal evidence—from around 1680 (see below). If it bears a title or any

imprint information, this is inaccessible on account of the sealed nature of the

casing, and the same is true of the only other known example of such an

artefact, the closely similar Common Cries of London sheet, now

preserved in an exactly comparable case in the Lilly Library of Indiana

University at Bloomington.

This month’s subject is an artefact recently acquired by the Yale Center for

British Art in New Haven which uses printed images to present a kind of moving

panorama of a strikingly modern kind. It comprises a leather-bound wooden box

with a screen and two rollers; by rotating the ends of these, it is possible to

view frame by frame through the 'screen' of the box a series of images which

were evidently cut from a sheet and pasted together into a long continuous

strip. This panorama, which has a truly popular appearance, must date—on

internal evidence—from around 1680 (see below). If it bears a title or any

imprint information, this is inaccessible on account of the sealed nature of the

casing, and the same is true of the only other known example of such an

artefact, the closely similar Common Cries of London sheet, now

preserved in an exactly comparable case in the Lilly Library of Indiana

University at Bloomington.

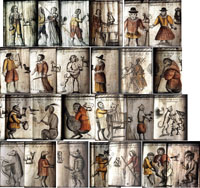

Here we display, first, a view of the box with its rollers and an image appearing within the screen, and second, an attempt to reconstruct the entire sheet from which the strip of images contained within it might have been formed: it seems likely that these might originally have been arranged in three, four, or perhaps five rows as shown here. This reconstruction is intended more for the convenience of displaying all the constituent images than as an assemblage in which I feel much confidence can be placed: however, since to take the object apart would be to destroy it, this is the closest to a reconstruction that we are ever likely to come.

Apart from the technical interest of the artefact in which it is preserved, the

series of images is of considerable importance for the study of late

seventeenth-century English popular culture, not least since it includes the

earliest depictions of such 'folk heroes', national stereotypes,

singeries and other drôleries as

Apart from the technical interest of the artefact in which it is preserved, the

series of images is of considerable importance for the study of late

seventeenth-century English popular culture, not least since it includes the

earliest depictions of such 'folk heroes', national stereotypes,

singeries and other drôleries as

A Graceless Knave

An Overdoing Knave

A flatring Knave

A Cheating Knave

Punchenello

Punchenello's Wife

Whiping Tom

Skiping Jone

A boy with puppies

Mother Louse

Time carys away the Pop[e]

A Baboon playing on a ho boy [oboe]

A Baboon drinks to a monkey

A monkey Smokes a pip

A Baboon plays on a lute

An Ape barbs 1 the Catt

A Catt in briches

A Catt fidleing and myce danceing

A Bear playing on a harp

A dog in a Coate

A hog in armor

Warping Jack Spanyard

Monsier Jack with his Stolen hens on his back

An Apish Mountebanck

An Apish Costermonger

There are thus no fewer than twenty-five individual scenes. The similar Common Cries of London sheet in the Lilly Library, which has already been noted, features twenty-nine individual criers, but this too unfortunately bears no imprint or other useful dating information, and is rather to be dated from the present sheet than vice versa. One of the smaller human heads that, together with small animals and birds, powder the background of the present sheet is a crowned male—certainly intended for Charles II—which therefore gives a date-range of 1660-1685 for the original print, but there are various other 'internal' facts that allow us to narrow down the date somewhat, and principally, the presence of ‘Whiping Tom’.

‘Whipping Tom’ is first heard of in print in 1681, in two broadside ballads (Whipping Tom, or, The deceitfull kinsman and Whipping-Tom turn'd citizen), and a prose sheet entitled Whipping Tom brought to light, and exposed to view, which at first sight, might seem to narrow the date of our print down to the years 1681-5, except that this latter sheet records that the present mysterious flagellant ‘is of the Generation of that Whipping Tom, that about Nine years since proved such an Enemy to the Milk-wenches Bums’, thus appearing to attest to the existence of another whipster, known by the same name, and operating c.1672 in the countryside. Other chronological indicators do not afford any greater precision—a half-length portrait of Mother Louse, the celebrated Oxford alewife, was engraved by David Loggan c.1665, 2 which may have brought her fame to a wider public than the university students for whom she catered, and the present image is certainly dependent on Loggan's, but that does not help us date the Yale sheet. Strictly speaking, then, we may perhaps date it between 1672 and 1685, but I feel happy enough to see it as originating in the earlier half of the 1680s.

It is interesting to see the designer copying five engravings made by Hollar back in the early 1640s amongst the sheet's twenty-five figures; the first four—as the captions indicate—are from his Pake of Knaves with trivial changes, the fifth, ‘Time carys away the Pop[e]’ was engraved as a single-sheet print by Hollar c.1641.

I cannot find any evidence for the independent existence of ‘Skiping Joan’ elsewhere, and it seems probable that she was invented merely as a (rhyming) female partner for Whipping Tom, and similarly provided with a three-thonged whip. ‘Punchenello's Wife’, on the other hand—known to us nowadays as ‘Judy’—and her husband, indeed, are a most interesting presence. Samuel Pepys seems to be the first to have noted a Punch-and-Judy show in England, in his diary entry for 9 May 1662, and references to the figure become more frequent from the later 1660s, though Punch's long-suffering wife does not appear to be mentioned until rather later than the date of our print, and these would appear to be the earliest-known English depictions of either. Punch is far from grotesque here, rather ordinary-looking, in fact, though short and sporting a small moustache; Judy is rather masculine in appearance, despite her full skirt.

Two of the figures appear to be foreign nationals, ‘Warping Jack Spanyard’ and the presumably French ‘Monsier Jack with his stolen hens on his back’, though neither figure is presented as a caricature visually. I am not clear in quite what sense the Spaniard is 'warping'—nor is it apparent from the image—unless he is meant to be distorting or contorting his body or features. He is, however, clearly derived from the undated Signiour Bobbadilli Puntado Cavalliro Puff or The Proud Vapouring Spaniard which bears the imprint, ‘London Printed Coulered and Sold by Ro:Walton at the Globe and Compasses, in St Paules Church-yard: on the North side’, over traces of an earlier one, and is preserved uniquely in the New York Public Library’s George Arents Collection on Tobacco. It may well be that the panorama artist’s ‘Monsier Jack’ similarly derives from another such xenophobic stereotype, perhaps a companion piece, but if so, it is unknown to me.

‘A boy with puppies’ perhaps derives from one of the two lost prints sold by Stent and his successor Overton, and advertised in their catalogues of 1662 and 1673 as ‘Boy with puppies’ and ‘Boy and puppies’, 3 and for all its diminutive size, this sketch is far from crude; the boy has lifted up his shift (thus exposing his nakedness) and cradles the puppies—four noses [?] can just be made out—in his shirt-lap, while the mother stands on her hind legs in her attempt to reach the pups, her swollen teats evident. The remaining twelve images are all of performing animals, and more than half of them singeries in the literal sense of that term. To these we must therefore now turn.

The taste for pictures of monkeys 'aping' human activities goes back well into the Middle Ages, of course, and the images in the margins of Gothic manuscripts, but the earliest such prints belong to the final quarter of the fifteenth century, and depict what was already a popular visual motif, the pedlar whose pack is rifled by apes while he sleeps, probably best known today in the version engraved by Pieter van der Heyden after Bruegel in 1562, which, as Janson pointed out, ‘served as the locus classicus of [the] motif from the 1560's until well into the seventeenth century’. 4 He further noted that the widely-travelled Thomas Coryate was puzzled as to the significance of a mural of the motif which he described in some detail as seen on the wall of the inn he stayed at in Lyons in 1608—interesting incidental evidence of the natural tendency for a seventeenth-century Englishman to assume such a representation must necessarily be 'emblematic' in some way:

‘on the South side of the wal of another court [of mine Inne], there was a very pretty and merry story painted, which was this: A certaine Pedler having a budget full of small wares, fell asleepe as he was travelling on the way, to whom there came a great multitude of Apes, and robbed him of all his wares while he was asleepe: some of those Apes were painted with pouches or budgets at their backes, which they stole out of the pedlers fardle climing up to trees, some with spectacles on their noses, some with beades about their neckes, some with touch-boxes and inke-hornes in their hands, some with crosses and censour boxes, some with cardes in their hands; al which things they stole out of the budget: and amongst the rest one putting downe the Pedlers breeches, and kissing his naked, &c. This pretty conceit seemeth to import some merry matter, but truely I know not the morall of it.’ 5

A series of sixteen plates etched c.1560 by Peeter van der Borcht seems to underlie, if not indeed to have originated, the increasing taste for similar singeries in the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Van der Borcht's Pedlar Robbed by Apes (on which Bruegel's design depends) is not part of this series, however, 6 a fact which attests to the pre-existing popularity of the theme, and, indeed, it seems likely that it was the very popularity of the Apes and Pedlar motif which gave Van der Borcht the idea for his series in the first place. His etching is a copy in reverse of van der Heyden’s after Bruegel which was first issued by Cock in Antwerp in 1562. Until as recently as 2003 there was no known English print of this very popular European motif, but in that year the British Museum acquired a print which is a slightly enlarged copy in reverse of Van der Borcht's engraving, bearing the imprint, ‘Are to be sold by Robert Pricke in White Cross street near Cripplegate Church RP excud.’, which was Pricke's address until 1676. (For a fuller discussion of this print, see Print of the Month, No. 26, January/February 2009.) The only other known impression, in the Douce collection in Oxford, bears an imperfectly erased imprint which can still be just made out as reading, ‘at the Ball in St Pauls Churchyard’, which was Pricke's address from c.1677.

The fourth plate in Van der Borcht's sixteen-plate series shows the apes feasting outdoors, and will doubtless have provided the prototype for the lost Monky's mock-feast listed in Stent's 1662 and Overton's 1673 catalogues. 7 The designer of the Yale Center panorama was nothing if not eclectic, and all seven of his ape compositions derive from singeries engraved by Coryn Boel (d.1668) after designs by David Teniers the Younger. Two of them, ‘An Ape barbs the Catt’ and ‘An Apish Mountebanck’, derive from his Barber-surgeon’s Shop, 8 but Boel also engraved a series of six singeries prints (plus title-page engraving) on which the remaining five ape scenes are based. The ‘Apish Costermonger’ and ‘A Baboon drinks to a monkey’ 9 are based on the print of the two apes playing backgammon; ‘A monkey smokes a pipe’—cf. also the print of the cat and pipe-smoking ape playing cards issued in 1646 and surviving uniquely amongst the Thomason Tracts in the British Library—is from that depicting two apes smoking; and ‘A Baboon plays on a lute’ derives from the print showing two monkeys making music. For his baboon oboist (‘A Baboon playing on a ho boy’)—especially given the length of the instrument—he probably took the hint from a detail of the title-page engraving. The taste for singeries was certainly still current c.1690 to judge from the clutch of catalogues of paintings put up for auction around that date, in which we read of ‘A piece of Monkeys shaving a Cat’, 10 and—if it is not the same item held over as unsold to two further sales—three lots described as ‘a Monkey trimming a Cat’, 11 as well as ‘Some Monkeys playing at Cards’, 12 ‘A Monkeys Feast’, 13 and ‘a p[ie]c[e] of monkeys smoaking and 2 prints’ 14 —a rare specification of prints for sale at auction, and presumably, prints of singeries.

I have not been able to point to a similarly precise source for the Yale panorama artist’s bear harpist, or the ‘Catt fidleing and myce dancing’. Some of these amusing animal images would have been familiar as shop or tavern signs, however, part of the popular art of the street; four Cat & Fiddles, for example, are attested for the 1660s (one a haberdasher's shop, recorded from 1667-77). 15 Though we cannot know whether any of these signs included ‘myce dancing’ while the cat fiddled, this addition would have been common enough, and is found, for example, on an English Delftware charger probably painted in Lambeth c.1730. 16 A tavern attested in Southwark in the 1650s and 60s had as its sign an ape seated and smoking a pipe. 17 In similar vein, Chettle refers in passing to a ‘signe of the Ape and the Urinall’ in Kind-harts Dreame (1592), as in the present ‘Apish Mountebanck’ scene. Precisely contemporary with the Yale print, A Hog in Armor is recorded in Fleet Street in 1678, 18 and was one of the inn-names Addison held up for ridicule in The Spectator of 2 April 1710:

‘Our streets are filled with blue boars, black swans, and red lions, not to mention flying pigs 19 and hogs in armour, with many creatures more extraordinary than any in the deserts of Africa.’ 20

But 'a hog in armour' is also a popular phrase, first recorded in English in Howell's English Proverbs (1659): ‘He looketh like a Hogg in armour’, and came to mean ‘an awkward or clumsy person, stiff and ill at ease in his attire’ (OED). Similarly, ‘[as proud as] a dog in a doublet’ was also listed by Howell, though this popular alliterative formula is found as early as 1577, and is perhaps relevant to the Yale sheet's image captioned ‘A dog in a Coate’—a sight presumably no less strange than that of ‘A Catt in briches’.

While prints might also function as toys, as things to amuse the children, of course, there is no guarantee that the Yale Center's ‘panorama’ of unknown title was designed for juvenile viewers. The fact that the ‘Overdoing Knave’ brandishes an alarming clyster-pipe and seems about to administer an enema to the diminutive dog beside him, or that in another Hollar-derived image, ‘Time carries off the Pope on his back’, does not preclude a youthful audience, however—sensibilities change, autres temps, autres mœurs!

Department of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the Yale Center for British Art. Reproduced by courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund. Dimensions of the panorama: H 10 cm x W 8 cm x D 3 cm; dimensions of the central viewing panel: H 8.5 cm x W 7 cm.

Footnotes

- 1.

- i.e. acts as barber to, shaves. Back to context...

- 2.

- F.G. Stephens, Catalogue of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum: Satirical and Personal Subjects, vol. 1 (1320-1689) (London, 1870), no. 797 (where dated too early); my dating is from Antony Griffiths, The Print in Stuart Britain 1603-89 (London, 1998), p. 198—the British Museum impression also happens to be one of the six now known bearing the 1672 imprimatur of Roger L’Estrange, ibid., p. 148. In his last known (posthumous) advertisement of 1691 Robert Walton was selling a pot sheet of Mother Louse. Loggan’s Mother Louse seems also to have been the inspiration for the anonymous and similarly burlesque engraved portrait of the Kentish Town alehouse-keeper, Mother Damnable, issued in 1676 (Stephens, op.cit., no. 1051). It is noticeable that the text to Mother Damnable opens, ‘Y’have often seen from (Oxford Tipling-house)/ Th’Effigies of Shipton fac’d Mother Louse’, surely implying the currency of the print by or after Loggan – cf. the copy made of it on the present Yale Center for Studies in British Art panorama. Back to context...

- 3.

- Alexander Globe, Peter Stent c. 1642-1665, London Printseller: A Catalogue Raisonné of His Engraved Prints and Books With An Historical and Bibliographical Introduction (Vancouver, 1985), cat. no. ?463. I note the title of a painting for sale at an auction held on 19 May 1690, where lot 252 was described as ‘A boy with a Bitch and Puppyes after Hungius’ [sic]: D.G. Wing, Short-Title Catalogue of Books Printed in England, Scotland and Ireland 1641-1700 (2nd ed., 3 vols., New York, 1982-94), C7626. Back to context...

- 4.

- H.W. Janson, Apes and Ape Lore in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (London, 1932), p. 224. The most recent discussion of this motif is J.B. Friedman, ‘The Peddler-Robbed-by-Apes Topos: Parchment to Print and back Again’, Journal of the Early Book Society, 11 (2008), pp. 87-120, and I thank the author for supplying me with an offprint. Back to context...

- 5.

- Thomas Coryate, Coryats Crudities (London, 1611), p. 66. Back to context...

- 6.

- Information from Ursula Mielke (personal communication), editor of the New Hollstein Peeter van der Borcht volume. Back to context...

- 7.

- A.M. Hind (with Margery Corbett and Michael Norton), Engraving in England in the 16th and 17th Centuries (3 vols., Cambridge, 1952-64), vol. 3, p. 70. Back to context...

- 8.

- F.W.H. Hollstein, Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts ca.1450-1700 (71 vols., Amsterdam, 1949-, in progress), vol. 3, s.v. Boel, no. 42. The series also exists copied in reverse by an anonymous engraver, an impression of his barber-surgeon’s shop is in the Wellcome Institute collection, ICV No 12166. Back to context...

- 9.

- cf. Abraham Holland's ‘A continued inquisition against Paper-Persecutirs’ in J. Davies, A scourge for Paper-persecutors (1624), sig. A2v, in which he discusses the sort of imagery to be found in the form of ballads and pictures pasted onto the wall of a typical ‘North-country’ inn [Yorkshire is mentioned], and includes ‘an Ape drinking Ale’. Back to context...

- 10.

- 26 May 1690, lot 196 [Wing C7644]. Back to context...

- 11.

- 2-3 June 1690, lot 190 [Wing C7674], 22-23 September, lot 312 [Wing C7628], and 11 November 1690, lot 159 [Wing C7630]. Back to context...

- 12.

- 2-3 June 1690, lot 250 [Wing C7674]. Back to context...

- 13.

- 15-17 July 1690, lot 25 [Wing C7676]. Back to context...

- 14.

- 17-19 March 1692, lot 159 [Wing C7664]. Back to context...

- 15.

- B. Lillywhite, London Signs (London, 1972), nos. 4515-4518, and 4514, respectively. Back to context...

- 16.

- See Sotheby's sale of Fine European Ceramics and Glass, London, 15 April 1997, lot 158. My thanks to Sheila O'Connell for bringing this to my attention. Back to context...

- 17.

- Lillywhite, London Signs, no.2431. Back to context...

- 18.

- Lillywhite, London Signs, no.8780. Back to context...

- 19.

- Curiously, there is no Flying Pig or similar sign listed in Lillywhite, London Signs, and—except for the tiny late medieval lead badges of winged boars—I know of no such image in English art before comparatively modern times. In his late 15th-century satirical poem, ‘Les Droitz Nouveaulx’, however, Coquillard refers in passing to a Parisian tavern named La Truye Vollant [The Flying Sow], which presumably boasted such a sign. The verbal image was certainly known in England by the early modern era, however; for contemporary continental representations see Malcolm Jones, The Secret Middle Ages (Stroud, 2002), pp. 153-4. Back to context...

- 20.

- Cited from J.Larwood and J.C. Hotten, English Inn Signs (New York,1985), p. 12. Back to context...