Print of the month

No. 26, January/February 2009

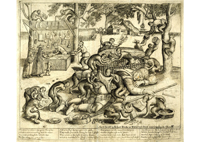

Pedlar Robbed by Apes

The taste for pictures of monkeys ‘aping’ human activities goes back

well into the Middle Ages, of course, and the images in the margins of Gothic

manuscripts. The earliest such prints, however, belong to the final

quarter of the fifteenth century, and depict what was already a popular visual

motif, the pedlar whose pack is rifled by apes while he sleeps, probably best

known today in the version engraved by Pieter van der Heyden after Bruegel in

1562, which, as Janson pointed out, ‘served as the locus classicus of

[the] motif from the 1560s until well into the seventeenth century’.

1

He further

noted that the widely-travelled Thomas Coryate was puzzled as to the

significance of a mural of the motif which he described in some detail as seen

on the wall of the inn he stayed at in Lyons in 1608—interesting incidental

evidence of the natural tendency for a seventeenth-century Englishman to assume

such a representation must necessarily be ‘emblematic’ in some way:

The taste for pictures of monkeys ‘aping’ human activities goes back

well into the Middle Ages, of course, and the images in the margins of Gothic

manuscripts. The earliest such prints, however, belong to the final

quarter of the fifteenth century, and depict what was already a popular visual

motif, the pedlar whose pack is rifled by apes while he sleeps, probably best

known today in the version engraved by Pieter van der Heyden after Bruegel in

1562, which, as Janson pointed out, ‘served as the locus classicus of

[the] motif from the 1560s until well into the seventeenth century’.

1

He further

noted that the widely-travelled Thomas Coryate was puzzled as to the

significance of a mural of the motif which he described in some detail as seen

on the wall of the inn he stayed at in Lyons in 1608—interesting incidental

evidence of the natural tendency for a seventeenth-century Englishman to assume

such a representation must necessarily be ‘emblematic’ in some way:

on the South side of the wal of another court [of mine Inne], there was a very pretty and merry story painted, which was this: A certaine Pedler having a budget full of small wares, fell asleepe as he was travelling on the way, to whom there came a great multitude of Apes, and robbed him of all his wares while he was asleepe: some of those Apes were painted with pouches or budgets at their backes, which they stole out of the pedlers fardle climing up to trees, some with spectacles on their noses, some with beades about their neckes, some with touch-boxes and inke-hornes in their hands, some with crosses and censour boxes, some with cardes in their hands; al which things they stole out of the budget: and amongst the rest one putting downe the Pedlers breeches, and kissing his naked, &c. This pretty conceit seemeth to import some merry matter, but truely I know not the morall of it. 2

A series of sixteen plates etched c.1560 by Peeter van der Borcht seems to underlie, if not indeed to have originated, the increasing taste for similar singeries in the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Van der Borcht's Pedlar Robbed by Apes (on which Bruegel's design depends) is not part of this series, however, 3 a fact which attests to the pre-existing popularity of the theme, and, indeed, it seems likely that it was the very popularity of the Apes and Pedlar motif which gave Van der Borcht the idea for his series in the first place. His etching is a copy in reverse of van der Heyden’s after Bruegel, which was first issued by Cock in Antwerp in 1562. Until as recently as 2003 there was no known English print of this very popular European motif, but in that year the British Museum acquired the present print which is a slightly enlarged copy in reverse of Van der Borcht's engraving, bearing the imprint, 'Are to be sold by Robert Pricke in White Cross street near Cripplegate Church RP excud.', which was Pricke's address until 1676. The only other known impression, in the Douce collection in Oxford, bears an imperfectly erased imprint which can still be just made out as reading, 'at the Ball in St Pauls Churchyard', which was Pricke's address from c.1677.

The 16-line caption to Pricke's version of the subject is perhaps worth quoting as a typical example of this sort of verse and will serve well enough to describe the composition:

In a country wheare Apes great Plenty bee

A Pedler was a traveling with his ware

You need not long looke which is hee

Hee lyes along 4 his gatt [i.e. bottom] is bare

And as hee slept the Apes gott to his pack

They make fine work among his toyes & glasses 5

They wonder at the sight of every knack

Which he had theare to please the co[u]ntry lasses

One powers [pours] out the mony from his purs

Another Royster [roisterer] pisses in his shooes,

Another in his capp doth skitt 6 that's worse

Yea each doe strive who should him most abuse

One blowes in's Nock 7 supposing of him dead

While sum doe hange his trinkets in the tree,

Another Ape is looking of his head

Another got a glase his face to see. 8

The fourth plate in Van der Borcht's sixteen-plate singeries series shows the apes feasting outdoors, and will doubtless have provided the prototype for the lost Monky's mock-feast prints listed in Stent's 1662 and Overton's 1673 catalogues. 9

A most important print recently acquired by the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven includes amongst its 25 miscellaneous individual scenes, an Apish Costermonger, apes smoking and drinking 10 (cf. the print of the cat and pipe-smoking ape playing cards issued in 1646 11 ), and various animal musicians—a baboon oboist and lutenist, a bear harpist, or a Catt fidleing and myce dancing—which probably also derive ultimately from such singeries. But the designer of the Yale Center panorama was nothing if not eclectic, and at least two of his ape compositions, those labelled An Ape barbs the Catt and An Apish Mountebanck, owe their appearance to the barber-surgeon’s shop of a mid-seventeenth-century Dutch singeries series engraved by Coryn Boel (d.1668) after David Teniers the Younger. 12 The taste for singeries was certainly still current c.1690 to judge from the surviving clutch of catalogues of paintings put up for auction around that date. We read of A piece of Monkeys shaving a Cat, 13 and—if it is not the same item held over as unsold to two further sales—three lots described as a Monkey trimming a Cat, 14 as well as Some Monkeys playing at Cards, 15 A Monkeys Feast, 16 and a p[ie]c[e] of monkeys smoaking and 2 prints 17 —a rare specification of prints for sale at auction, and presumably, prints of singeries.

British Museum 2003,0531.4. Dimensions of original: 266 mm x 310 mm.

Footnotes

- 1.

- H.W. Janson, Apes and Ape Lore in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (London, 1932), p. 224. The most recent discussion of this motif is J.B. Friedman, ‘The Peddler-Robbed-by-Apes Topos: Parchment to Print and Back Again’, Journal of the Early Book Society, 11 (2008), pp. 87-120, and I thank the author for supplying me with an offprint. Back to context...

- 2.

- Thomas Coryate, Coryats Crudities (London, 1611), p. 66. Back to context...

- 3.

- Information from Ursula Mielke (pers. comm), editor of the New Hollstein Peeter van der Borcht volume. Back to context...

- 4.

- To 'lie along' means to 'lie full-length, lie outretched on the ground'; given that the pedlar in this print appears to be a young man, it is conceivable that the 'one plat of the Boy lying along' as it appears in Stent's 1662 advertisement is the same subject, even perhaps the earliest state of the present print, before acquired by Pricke (Alexander Globe, Peter Stent, c. 1642-65, London Printseller (Vancouver, 1985), no. 464)—though the absence of any mention of the apes perhaps makes this unlikely. Back to context...

- 5.

- Perhaps 'spectacles' here. Back to context...

- 6.

- i.e. ‘shit’. This is a considerable antedating of 'skit' v.1 in OED, where this form of 'shit' is not attested until 1805. Back to context...

- 7.

- i.e., blows in between his buttocks. Back to context...

- 8.

- i.e., a mirror to see his (own) face in it. In the previous line, ‘looking of his head’ means ‘examining his head’. Back to context...

- 9.

- Globe, Peter Stent, no. 472. Another singerie was engraved by Robert Vaughan as the frontispiece to the Age of Apes, the second part of Richard Brathwaite's The Honest Ghost (1658): A.M. Hind (comp. Margery Corbett and Michael Norton), Engraving in England in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Vol. 3: The Reign of Charles I (Cambridge, 1964), p. 70. Back to context...

- 10.

- cf. Abraham Holland's A continued inquisition against Paper-Persecutirs in J. Davies, A Scourge for Paper-persecutors (London, 1624), sig. A2v., in which he discusses the sort of imagery to be found in the form of ballads and pictures pasted onto the wall of a typical 'North-country inn' ['Yorkshire' is mentioned], and includes 'an Ape drinking Ale'. Back to context...

- 11.

- BM Satires no. 658: F.G.Stephens, Catalogue of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum: Satirical and Personal Subjects, vol. 1 (1320-1689) (London, 1870), p. 363. Back to context...

- 12.

- Hollstein (Boel) 42. Back to context...

- 13.

- 26 May 1690, lot 196 [Wing C7644]. Back to context...

- 14.

- 2-3 June 1690, lot 190 [Wing C7674], 22-23 September, lot 312 [Wing C7628], and 11 November 1690, lot 159 [Wing C7630]. Back to context...

- 15.

- 2-3 June 1690, lot 250 [Wing C7674]. Back to context...

- 16.

- 15-17 July 1690, lot 25 [Wing C7676]. Back to context...

- 17.

- 17-19 March 1692, lot 159 [Wing C7664]. Back to context...